Sexual Violence and Harassment in Nova Scotia Schools

A review of school incident data chronicling sexual assaults, harassments and misconducts

In the Spring of 2023 Nova Scotia Parents for Public Education published a Padlet asking people to send in their anonymous experiences in and around the public school system, initially centered on the issues of violence and bullying. Some of those experiences shared described alarming incidents of a sexual nature.

Trigger warning: this article will attempt to show statistics on sexual assaults, harassments and misconducts in schools within Nova Scotia.

Transcriptions from the Padlet have been edited for grammar and clarity.

“Three years ago, I broke up a fight between 2 students. One sexually harassed the other and so he punched that student in the face, causing a bloody nose. Administration did nothing because ‘it was their first offence.’”

“I had a student ask me to perform a sexual act on him. He threatened to *** multiple female students who were told to avoid and ignore him.”

“As a parent, my child has told me of school incidents where assault and sexual assault happen often to other kids, sometimes in class, and the teachers don’t or can’t do anything, and the child being assaulted gets punished. I have heard stories of sex trafficking at the school multiple times.”

“My daughter endured being harassed physically and sexually by a fellow classmate and they refuse to do anything about it even after filing 2 police reports about it. It was the same boy every time. He is still in her class to this day and she is told to ‘just ignore him’ or ‘pretend he isn’t there’ because they don’t want to take opportunities away from him.”

These stories are heartbreaking. They’re hard to read. They’re hard to comprehend. We want to be as fact-positive as we can, so we will let those words speak for themselves and concentrate on the data we know about sexual behaviours in schools.

FOIPOP 2021-02089-EDU outlines the number of sexual assaults in high schools from 2018-2019 through 2020-2021 school years:

2018-2019: 38 sexual assaults

2019-2020: 34 sexual assaults

2020-2021: 18 sexual assaults

Until now, this was the only narrow window into documented sexual behaviours in our schools. One of our members submitted Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy (FOIPOP) Act request number 2023-01285-EDU which asked for all incidents of sexual assault, sexual harassment and sexual misconduct in Nova Scotia schools from the 2017-2018 to 2022-2023 school years, grouped by Regional Centre for Education. This is slated to be published publicly on November 16, 2023 via the province’s OpenInformation portal.

Summarized statistics of that FOIPOP release are as follows. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development does not publish lower numbers than 11 due to privacy reasons. Why? Evidently, it’s easier to determine someone’s identity if the number is low. Any number between 1 and 10 will be signified by blanks. Any number omitted by the FOIPOP response is assumed to be zero. This does not affect the sexual harassment and sexual misconduct summaries much, however insight into sexual assault totals is very much blurred. Please note, this is not what was asked for. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development provided an additional breakdown by grade which unfortunately makes finding the actual totals impossible.

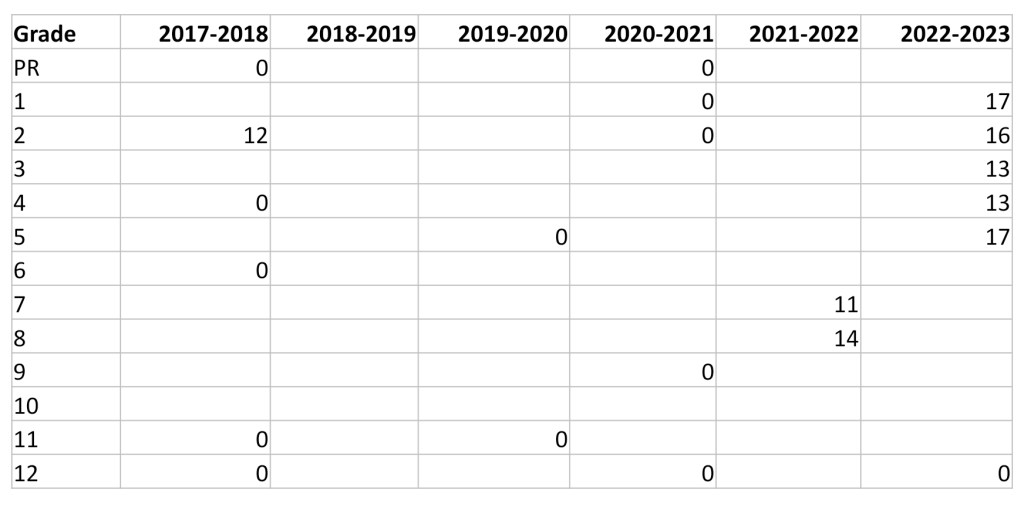

Sexual Assault

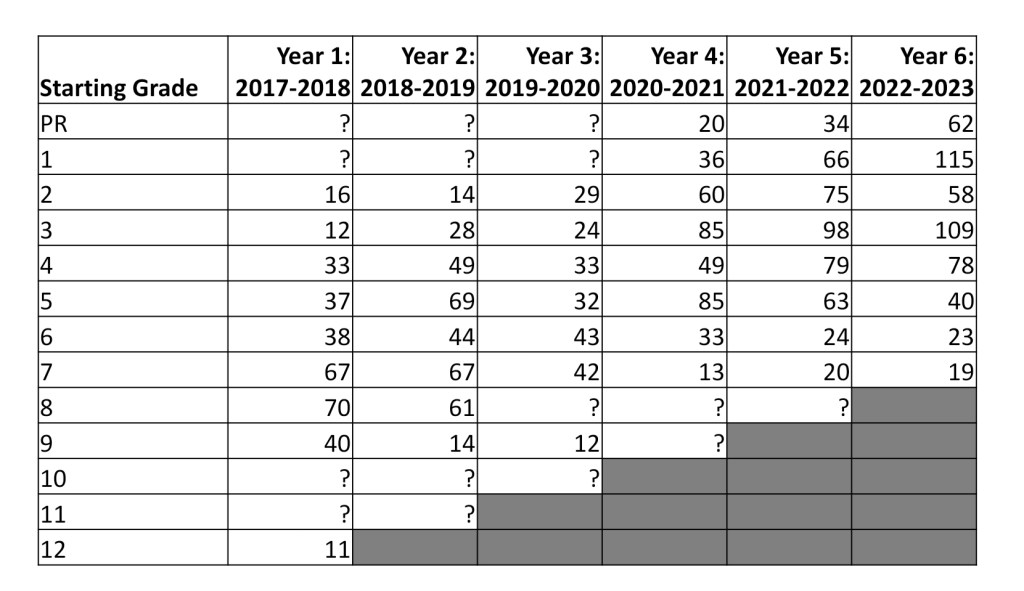

The data given in this latest FOIPOP offers a reader more questions than answers. The fact that grades 1 through 5 contain the bulk of reportable numbers for 2022-2023 should be concerning. And only once was there a grade with more than 10 sexual assaults in the previous five years.

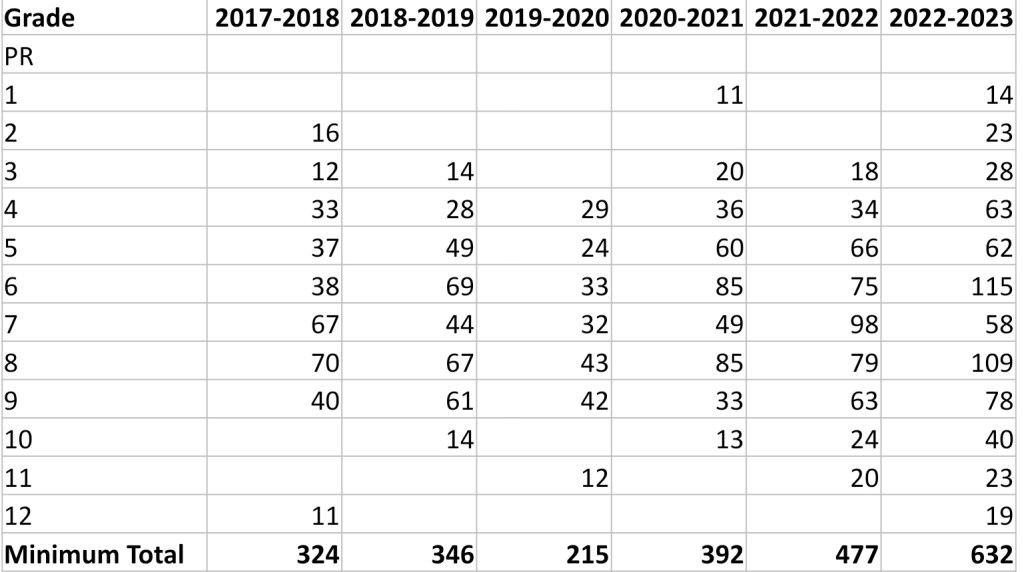

Sexual Misconduct

The numbers for sexual misconduct are far easier to consume, simply because of the low amount of data points withheld for privacy reasons. Comparing 2017-2018 with 2022-2023 is fairly straightforward considering both have grade 12 totals which are largely withheld. If we cancel out grade twelve, we have an increase of 31.48% between those two years. The drastic reduction in 2019-2020 and 2020-2021 coincides during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

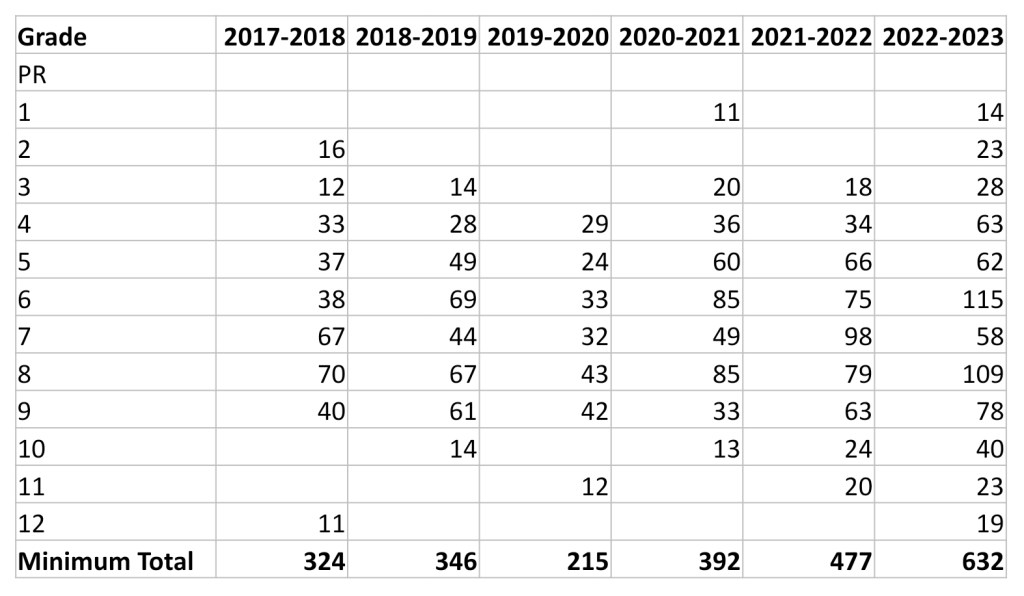

Sexual Harassment

Regarding sexual harassment data, there’s a few things to note:

Sexual harassment appears to be more pronounced between grades 3 and 9

Between 2017-2018 and 2022-2023 there’s a minimum 95% increase

Between 2021-2022 and 2022-2023, there’s a 32.5% increase

What do these numbers mean paired with testimonies from parents and staff at the beginning of this article?

In terms of understanding the overall rate, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development also provided the yearly enrollment totals for each Regional Centre for Education. That’s fair. The total enrollment for 2022-2023 was 129,121 students.

We’ll use the 88 confirmed incidents of sexual assault in our schools in 2022-2023. That number omits data from six grade levels. We know the number isn’t zero for those, so it could be 1 through 10. There are 88 known sexual assaults for 2022-2023. A rate per 100,000 of 68.

Then we add the unknown numbers, which would be anywhere from 1 through 10.

A minimum of 1 sexual assault per grade could bring the rate per 100,000 to 73.

A maximum of 10 sexual assaults per grade could bring the rate to 114 per 100,000.

Somewhere in there is the truth.

The most recent rate of sexual assault for Nova Scotia is 97 per 100,000. Ten years ago, it was 70. When Minister of Education Becky Druhan refers to schools being a “microcosm of society,” she’s not wrong. Obviously, there are societal influences at play. That means we must work harder to ensure those negative influences are dealt with openly and honestly within the systems we have. This peek into what schools are really like is a start.

Patterns in behaviour paint a grim picture

It’s not hard to spot patterns in data.

All three categories of sexual assault, harassment and misconduct appear to be increasing almost every year.

If you look at when a group of students that started a grade then you can see how those people have progressed year over year. You can almost predict the growth rate for future years based on how the data “moves.”

For example, in this data set you have students starting in grade three back in 2017-2018. The amount of sexual harassment incidents exploded to 109 last year when they were in grade 8. That’s an 800% increase for largely the same set of students. This year, as those students are in grade 9, we would expect to see those rates climb even higher. The same goes for grade 8 (a 262% increase between 2017-2018 and 2022-2023). Last year’s grade 7 and grade 6 have a 219% and 210% growth in sexual harassments over 2020-2021. It would be higher if we had the real numbers from back in 2017-2018, but we don’t.

Is this a sign of a lack of supports? The removal of unassigned instructional time? Fallout from changes in the education system due to the COVID-19 pandemic? Inflation? Cost of living increases? The housing crisis? The lack of a school lunch program paired with overall economic uncertainties? Those early formative years in elementary schools are important. It may explain why sexual harassments drop with older students who started grade five or higher in 2017-2018. Something happened. Perhaps a mix of all the above. These kids need help. They need to learn to put their phones away and stop filming someone being harassed. These kids need bystander training. They need to be taught how to stand up for each other and to protect each other. This simply can’t wait any longer.

We don’t have all the answers. We can ask the province for data. We can push back and say “this isn’t the data we asked for.” Most importantly, we can spot patterns in the data enough to logically assume these numbers will be worse this current school year.

We shouldn’t be the ones leading this charge, but we are. We shouldn’t be the ones pointing out these trends and sounding the alarms on data that’s never been publicly released. Our elected leaders should already be able to see the full numbers and understand the full scope. They need to put solutions in place to prevent the need for parents and school staff to air their grievances about a broken system anonymously, especially when it comes to discussing incidents of sexual assault and sexual harassment regarding the children our system has a duty of care to protect.